This post is part of a series exploring the (very) basics of iterative development using the example of a simple Snakes and Ladders-like game. Links to each post in the series will be added to the index page.

For a while now I’ve wanted to write a Snakes and Ladders-style game for my daughter, both to be a nice nerdy Dad, and to practice some dev stuff. I was going to create "Warps and Wormholes", but firstborn was adamant she wanted fairies involved. And so I’ve ended up with "Garden Race", which is going to be a race for players to make it to one end of the garden aided by fairies, butterflies and other girlie stuff, while hindered by lizards, hoses, and other less-girlie stuff.

I intend to use iterative development for this project – I’ll start off with a thin slice of functionality and keep adding to it to build up a semi-usable game. This should accomplish two things: first, showcase my own ineptitude, and second, to help improve my TDD and development skills. While I’m not exactly sure how far I’ll get with this project (free time is short at present), I can commit to being fairly honest during this process. If and when I stuff up, I’ll write it down (I might excuse myself a quick spike here and there so the posts don’t get bogged down to much, but the stuff ups will stay).

Note: MS has a free game design version of Visual Studio that might be useful if your aim is to make a good game for your kids (instead of just playing with dev stuff). There are also a few open source frameworks out there (like Childsplay).

For my starting point, I began with a rough solution structure (main Game project and a test project), chucked it in a local SVN repo, and setup some of the tools I’d need. I’m trying using a /src based configuration just for kicks, and might try nant just for something different. I am also trying XUnit.Net, instead of my usual NUnit test framework.

Requirements

Our customers, i.e. my firstborn (after some prompting) and I, want a Snakes and Ladders-type game involving fairies and other garden-dwelling folk. Here is the basic statement of what we want:

"Garden Race is a computer-based board game. Players take it in turns to roll a die, and then move the corresponding number of squares on the board. If the player lands on a square featuring a garden creature of obstacle at the end of their turn, then that creature or obstacle will move the player to a connected square on the board. The first player to reach the bottom of the garden (the end of the board) wins. We want fancy 3D graphics, surround sound, and it has to be ready yesterday."

Ever noticed how hard it is to succinctly describe a simple concept, even something as simple as this? Let’s try and remove some ambiguity by boiling things down into user stories.

- A player can roll the die, and then move that many spaces along the board.

- A player that ends his or her turn on a “feature square” (a square containing a creature or obstacle), will be moved to the square connected with that feature.

- There can be 1-4 players, and each player has their turn in sequence.

- A player that reaches the final square wins the game.

That should probably be enough to get us going.

Planning and design for this iteration

In the spirit of iterative design we are going to first try to deliver a slice of functionality. As we are currently unsure of exactly how to present the customer with fancy 3D graphics and sound (at this stage the dev team (me) would like to try WPF or QT4, but we don’t know all the requirements yet), let’s focus on the core game functionality, which is pretty much captured by the user stories above.

For our first iteration we’ve agreed with the customer to deliver stories 1 and 4, which is basically a single player rolling a die and moving to the end of the board. Exciting game huh? But it should reveal some basics of how the game mechanics work, so it seems a safe place to start.

If we are picking nouns for potential classes in our game we might come up with Player, Die, Square, and Board, but we’re definitely not going to use nouns as a basis for our design. A nice place to start might just be a Game or GameEngine class. What tests could we come up with for our first story?

- A player should not be on the board until the roll the die and move.

- A player that rolls a 4 should then be on the 4th square from the start.

- A player that rolls a 2, and then a 6, should be on the 8th square from the start.

- The game should finish once the player reaches the end.

We currently don’t have enough information to implement all of this. How many squares are there on the board? What is the maximum value of the die used? What happens if the player is one square from the end, and rolls a 3? The first couple of points we will check with the customer, but it doesn’t really affect our design. Let’s test for the last case though, and we’ll check with the customer if our assumption is correct:

- A player that is one square from the end, and rolls a 3, should win the game.

Before we jump into this iteration, I’d be really interested to hear any up-front design ideas you have for this. If you were going to draw a UML class diagram or write up some CRC cards, what classes, data and relationships would you have? I’ve got my own ideas, but I don’t want to influence my iterative design process too much at this point, nor do I want to deliberately come up with a shoddy upfront design and then marvel at how well my iterative design (hopefully) turns out. Please feel free to leave your design ideas in the comments or email me.

Right, let’s start.

First tests

Let’s look at the second test on our test list. It looks like an easy thing to do and should help us learn a little about the problem domain.

public class GameSpec {

[Fact]

public void Player_should_be_on_fourth_square_after_rolling_a_four() {

var game = new Game();

game.Roll(4);

Assert.Equal(4, game.CurrentSquare);

}

}

Not going to keep much of this, I’m pretty sure of that. But we need to start somewhere. By the way, if you aren’t familiar with XUnit.Net, [Fact] == [Test]. Now let’s pass the test:

public class Game {

public int CurrentSquare;

public void Roll(int dieValue) {

CurrentSquare += dieValue;

}

}

Now let’s test two rolls, which is the third test on our list.

[Fact]

public void Player_should_be_on_eight_square_after_rolling_a_two_then_a_six() {

var game = new Game();

game.Roll(2);

game.Roll(6);

Assert.Equal(8, game.CurrentSquare);

}

This works without change, as we jumped straight to an obvious implementation for Roll(). We could have taken smaller steps and initially used CurrentSquare = dieValue; to pass the first test, the updated it to pass the second test, but we don’t need to do that unless we aren’t really sure how to proceed.

Let’s add a third test to make sure the player starts off the board, or square 0.

var game = new Game(); Assert.Equal(0, game.CurrentSquare);

Again, this passes without modification. We also have a test on our list about finishing the game. We don’t have too much information about how this works, so let’s look at what we can test.

[Fact]

public void Game_should_finish_when_player_reaches_end_of_board() {

const int boardSize = 10;

var game = new Game(boardSize);

game.Roll(boardSize);

Assert.Equal(10, game.CurrentSquare);

Assert.True(game.IsFinished);

}

This introduces two new concepts: board size, and the game state as finished or not finished. To get this to compile we need to add non-default constructor to Game, which means we also need to explicitly add a default constructor if we want to stop our other tests from breaking. We also need to add an IsFinished property to Game. The following implementation compiles and passes all the tests.

public class Game {

public int CurrentSquare;

public Game(int boardSize) {}

public Game() {}

public bool IsFinished {

get { return true; }

}

public void Roll(int dieValue) {

CurrentSquare += dieValue;

}

}

The IsFinished implementation obviously stinks, so let’s also add a test around unfinished games.

[Fact]

public void New_game_should_be_unfinished() {

const int boardSize = 10;

var game = new Game(boardSize);

Assert.False(game.IsFinished);

}

I first did a trivial implementation:

public bool IsFinished {

get { return CurrentSquare == 0; }

}

Which failed both my IsFinished tests. Oops, that should be CurrentSquare != 0. Tests now pass, but the implementation still stinks. Let’s try this one:

[Fact]

public void In_progress_game_should_be_unfinished() {

const int boardSize = 10;

var game = new Game(boardSize);

game.Roll(5);

Assert.False(game.IsFinished);

}

Which we can pass with this:

public class Game {

private readonly int boardSize;

public Game(int boardSize) {

this.boardSize = boardSize;

}

public bool IsFinished {

get { return CurrentSquare >= boardSize; }

}

//...[snip]...

The last test on our list so far is to see what happens when we overrun the last square on the board.

[Fact]

public void Game_should_still_finish_when_player_overruns_last_square() {

const int boardSize = 10;

var game = new Game(boardSize);

game.Roll(boardSize + 2);

Assert.True(game.IsFinished);

}

This passes because we used >= for the CurrentSquare/boardSize comparison. One thing I haven’t been doing is the refactor step of the TDD red-green-refactor process. Let’s look at Game:

public class Game {

private readonly int boardSize;

public int CurrentSquare;

public Game(int boardSize) {

this.boardSize = boardSize;

}

public Game() {}

public bool IsFinished {

get { return CurrentSquare >= boardSize; }

}

public void Roll(int dieValue) {

CurrentSquare += dieValue;

}

}

Not much to refactor there, right? The tests have some duplication in the Game setup though. And the default constructor of Game looks fairly useless. Normally I would just whack that into a [SetUp] method, but XUnit.Net discourages this as it can make for non-obvious test contexts. My GameSpec tests currently want to execute in the one test context – a new Game with 10 squares. It seems reasonable that my GameSpec HAS-A context, so let’s add a game as a field with a descriptive name. I can then replace the game initialisation in each test with a simple reference to newTenSquareGame, and get rid of Game’s default constructor.

public class GameSpec {

private readonly Game newTenSquareGame = new Game(10);

//...[snip]...

[Fact]

public void Game_should_finish_when_player_reaches_end_of_board() {

newTenSquareGame.Roll(10);

Assert.Equal(10, newTenSquareGame.CurrentSquare);

Assert.True(newTenSquareGame.IsFinished);

}

//...[snip]...

If we start having lots of different contexts or complicated contexts we may want to revisit this, but the whole test fixture reads fairly well for now. Full disclosure: before this approach I mucked around with some crazy test structure ideas I have regarding tests and test contexts. I’m omitting that from this post as it was mainly for personal interest rather that something I would normally do.

So what’s next? Our test list is empty, and we seem to have completed most of our first iteration, stories 1 and 4. If you remember, these basically covered moving a single player around the board, and being able to finish the game. This isn’t really something we can show our customer though. You don’t go showing a youngin’ a bunch of unit tests when they are expecting a fairyised version of Snakes and Ladders. And we haven’t even dealt with the concept of "rolling a die", we have just assumed a value. But we seem to have the basic functionality we promised for this iteration.

Customer demo

To finish this iteration, let’s write a console app that will allow our customer to run through the current game logic. Here’s what I’m thinking of:

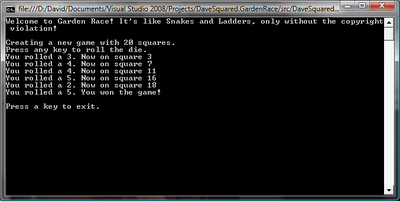

Creating new game with 20 squares. Press a key to roll the dice. You rolled a 4. Now on square 4. You rolled a 6. Now on square 10. ... You rolled a 2. You won the game!

At first I was thinking about creating a GameController class and writing some tests around that, then calling that from a simple console app. But we don’t need that yet. So let’s just do the simplest thing that will work for our demo. And because it is slapped together and not designed to specific requirements, let’s just promise not to use any of this code in the actual product.

namespace DaveSquared.GardenRace.ConsoleFrontEnd {

class Program {

private static readonly Random random = new Random();

static void Main(string[] args) {

Console.WriteLine("Welcome to Garden Race! It's like Snakes and Ladders, only without the copyright violation!");

Console.WriteLine();

const int numberOfSquares = 20;

const bool interceptKey = true;

Console.WriteLine("Creating a new game with " + numberOfSquares + " squares.");

var game = new Game(numberOfSquares);

Console.WriteLine("Press any key to roll the die.");

while (!game.IsFinished) {

Console.ReadKey(interceptKey);

var dieRoll = GetDieValue();

game.Roll(dieRoll);

var currentState = (game.IsFinished) ? "You won the game!" : "Now on square " + game.CurrentSquare;

Console.WriteLine("You rolled a " + dieRoll + ". " + currentState);

}

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine("Press a key to exit.");

Console.ReadKey(interceptKey);

}

static int GetDieValue() {

return random.Next(1, 6);

}

}

}

A now for the moment of truth:

Fantastic! Assert.That(this_game_rocks).SaidWith(sarcasm)! On the other hand, it took about 12 minutes to code this iteration up as well as write out tests (plus lots of time for me to type out this narrative), and our story list made it clear when we could stop. So let’s go show our customers. I’m sure they’ll be impressed…

Download

You can browse through or download this tremendously exiting code from davesquared.googlecode.com.