This post is part of a small series on .NET ORM tools. You can find the rest of them here.

As part of my continuing efforts to fragrantly misuse a number of .NET ORM tools, here is my effort with LinqToSql. The usual proviso applies: all of this is really quick and hacky, as it is just to get a little familiarity with the tool rather than to uncover any "best practices" or similar.

Scene refresher

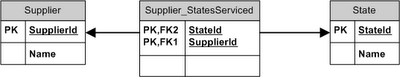

I have a table of suppliers, and a table of states (or provinces, territories, prefectures etc.). Both suppliers and states have names, which are stored as strings/varchars, and IDs, which are stored as Guids/uniqueidentifiers. Each supplier can service many states. So we have a simple many-to-many relationship between the two main entities. It looks a bit like this:

I am using Aussie states for my tests, so I have populated the State table with the following names: NSW, VIC, QLD, TAS, SA, WA, ACT, NT.

Setting up LinqToSql

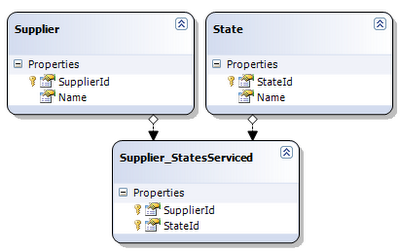

I created a new C# class library project, then added a LinqToSql Classes project item, which I named WorkshopDb.dbml. In true Microsoft style, you simply drag and drop the tables from the database onto the designer, which generates the necessary classes for you:

This adds an app.config file to the project, containing the relevant connection string. We are now ready to go!

Populating the database

As per my previous posts, I’ll a test fixture to run the remainder of the code. After cleaning out my little database again, I’ll add a method to encapsulate the process of creating a supplier and mapping the states it services:

private static void createSupplier(String name, String[] statesServiced) {

WorkshopDbDataContext db = new WorkshopDbDataContext();

Supplier supplier = new Supplier();

supplier.SupplierId = Guid.NewGuid();

supplier.Name = name;

List<State> states = (

from state in db.States

where statesServiced.Contains(state.Name)

select state

).ToList();

states.ForEach(

state => supplier.Supplier_StatesServiceds.Add(

new Supplier_StatesServiced() {

SupplierId = supplier.SupplierId,

StateId = state.StateId

}

));

db.Suppliers.InsertOnSubmit(supplier);

db.SubmitChanges();

}

As with SubSonic, LinqToSql does not automatically let me traverse the many-to-many relationship, but the new ForEach method makes it pretty easy to map each state to the supplier.Supplier_StatesServiceds collection (man, I really should have aliased that mapping table first).

We can now use that method to add the following test data:

createSupplier("Dave^2 Quality Tea", new string[] { "NSW", "VIC" });

createSupplier("ORMs'R'Us", new string[] { "NSW" });

createSupplier("Lousy Example", new string[] { "TAS", "VIC" });

createSupplier("Bridge Sellers", new string[] { "QLD" });

Querying the data

Let’s run through the usual tests. First, getting a list of all suppliers.

[Test]

public void Should_be_able_to_get_all_suppliers() {

WorkshopDbDataContext db = new WorkshopDbDataContext();

var suppliers = from supplier in db.Suppliers select supplier;

Assert.That(suppliers.Count(), Is.EqualTo(4));

}

So far so good. Now let’s get all suppliers with an "s" in their name.

[Test]

public void Should_be_able_to_get_all_suppliers_with_s_in_their_name() {

WorkshopDbDataContext db = new WorkshopDbDataContext();

var suppliers = from supplier in db.Suppliers

where supplier.Name.ToLower().Contains("s")

select supplier;

Assert.That(suppliers.Count(), Is.EqualTo(3));

}

And finally, let’s navigate over the supplier-state relationship to get all suppliers that service NSW:

[Test]

public void Should_be_able_get_all_suppliers_that_service_NSW() {

WorkshopDbDataContext db = new WorkshopDbDataContext();

var suppliers = from supplier in db.Suppliers

join servicedState in db.Supplier_StatesServiceds

on supplier.SupplierId

equals servicedState.SupplierId

where servicedState.State.Name == "NSW"

select supplier;

Assert.That(suppliers.Count(), Is.EqualTo(2));

}

Pretty straight forward. This actually generates very similar SQL to the NHibernate example, but because I never actually get a list from the suppliers expression, the suppliers.Count() call actually uses SELECT Count(*) ... (I believe you can do similar queries in both NHibernate and SubSonic). The following is roughly what is executed via sp_executesql:

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM [dbo].[Supplier] INNER JOIN [dbo].[Supplier_StatesServiced] ON [Supplier].[SupplierId] = [Supplier_StatesServiced].[SupplierId] INNER JOIN [dbo].[State] ON [State].[StateId] = [Supplier_StatesServiced].[StateId] WHERE [State].[Name] = @p0

Vague semblance of a conclusion

LinqToSql was extremely easy to use, especially in the initial configuration department. Like NHibernate, the query syntax takes a bit of getting used to, but it is something that becomes familiar fairly quickly.

I should point out that both SubSonic and NHibernate currently target the .NET 2.0 world, so the "Language INtegrated Query" part of LinqToSql was always going to give LinqToSql a bit of an expressiveness advantage. If you are a big fan of LINQ queries, they may be coming to an ORM tool near you in the not-too-distant future now that .NET 3.5 has been released. That said, I still quite like how the query criteria works in the NHibernate example.

I also noticed that NHibernate was more domain model (i.e. classes) focused, whereas the LinqToSql query for retrieving all the suppliers that service NSW was more data-schema focussed (using the JOIN construct rather than have a working knowledge of the relationship). This isn’t meant as praise or criticism of either, just a difference in the approaches. As a quick side note, I believe the ADO.NET Entity Framework is meant to have more advanced support for many-to-many relationships.

So far I’ve actually felt SubSonic was the most difficult to use for this particular scenario, but this is largely a result of the contrived example I used. I have used SubSonic a few times and in general it is exceptionally straight forward to get working.

As I was mainly looking into how each tool tackled this particular scenario, I have not gone into the different architectural approaches of the tools (ActiveRecord vs. DataMapper, implications for testability and persistence ignorance etc.). It’s definitely worth looking into this side of things if you are unfamiliar with the tools. Ian Cooper has a great post on some of these issues as applied to LinqToSql.

That’s it for now. Good luck on your ORM travels!